This week, I attended a lunch presentation during Tech Week Grand Rapids titled “From Disruption to Opportunity: AI and the Future of Work.”

If you’ve spent any time around events like Tech Week, you’ll notice that the word future shows up everywhere. Future of Work. Future of Education. Future of Cities. The future this, the future that.

But what struck me was that, despite all the talk, no one actually defined what they meant by future. When, exactly, is “the future”? Tomorrow? Next year? Twenty years from now?

So, during the panel discussion, I asked: “When you’re talking about the future within your organizations, what timeframe does that mean?”

Their answer: three to five years.

In the context of a conversation about how to develop talent in a world disrupted by AI, that timeframe caught me off guard.

⸻

Why This Matters

Three to five years is a reasonable horizon for executing on a piece of strategy. It’s a solid window for making plans, aligning resources, and measuring results. But calling it the future? That feels incomplete.

To me, the future is at least 20 years out—maybe longer. That’s the timescale on which cultural norms, technologies, and systems reshape our lives.

We don’t have to look far for examples. We complain today about the effects of social media on our children, yet almost no one speculated 20 years ago about what a world with constant, ubiquitous, handheld social media would look like. We didn’t imagine the downstream effects on attention, civic discourse, or mental health.

Instead, we rushed to adopt. New technology often begins as a “solution in search of a problem,” and then spreads because it’s shiny, convenient, or profitable. That’s how social media embedded itself in our lives before we even understood what it would mean.

Now, AI is following the same pattern. It’s already reshaping our work, our trust in media, and even our understanding of creativity. But instead of pausing to articulate a preferable future (the one we want to live in) leaders in business, government, and education are largely talking about use cases.

We’re racing toward adoption because competitors are doing it, or because customers expect it. Those may be valid pressures, but without a larger frame, it feels like being trapped in a car without brakes, barreling toward a cliff. Instead of asking “How do we avoid going over the edge?” too many of us are preoccupied with “What can we get done inside the car before it happens?”

⸻

The Order of Effects

Here’s the juxtaposition that unsettles me:

So many organizations talking about AI sound less like they’re shaping the future, and more like they’re defending themselves against a present-day threat. Their strategies are reactive, not visionary.

That’s because most people and organizations default to responding to the future instead of creating it.

Futures Thinking flips that script. It often begins not at three years, but at 20. Why? Because when you look that far ahead, you’re freed from the gravitational pull of today’s problems. You can ask: What do we actually want to be true?

There’s a beautiful etymological link here: the word supervision comes from super (over) and videre (to see). To have supervision is to see over and beyond. Futures Thinking is a form of supervision—it requires lifting your eyes beyond the immediate obstacle.

Think about riding a bike. If you lock your eyes on the one rock in the path, it becomes almost impossible not to hit it. To steer smoothly, you have to keep your gaze forward, scanning for where you want to go.

Organizations face the same dilemma. By staring at short-term threats, they often drive straight into them. By contrast, Futures Thinking encourages us to raise our eyes and chart a longer path.

I understand the tension here. Organizations are accountable to investors, boards, or shareholders. They need to produce returns in the short term. But I’d argue they also have an ethical responsibility to speculate about the long term—to consider the world they are helping to create, not just the next quarter’s results.

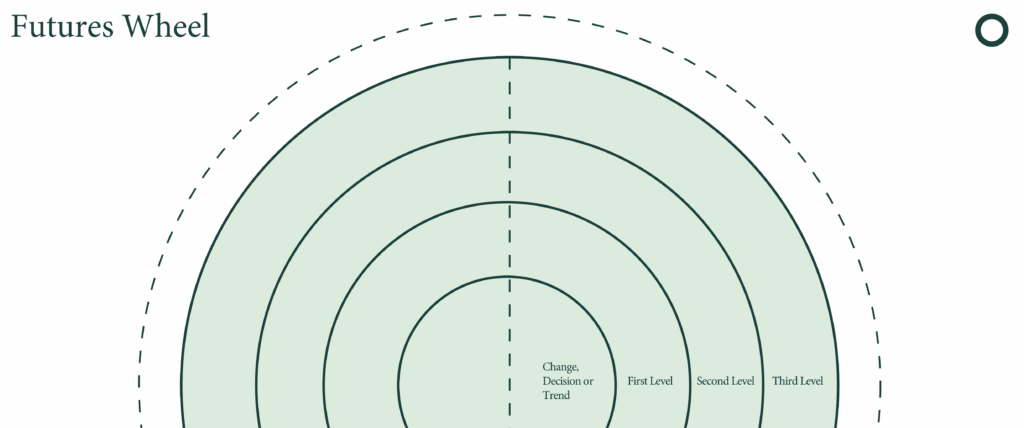

And this isn’t impossible work. Tools exist to help. One of the simplest is the Futures Wheel. You start with an innovation or decision in the center, then map out its first-order consequences (both positive and negative). From there, you map the consequences of those consequences, and so on. In a few cycles, you can see ripples of impact that extend well beyond the initial decision.

With AI, a Futures Wheel might begin with: “We adopt AI tools in our hiring process.” First-order effects could include faster screening, cost savings, or efficiency. But second-order effects might include bias amplification, talent pipeline shifts, or new regulatory scrutiny. Third-order effects could reshape trust in institutions or workforce diversity decades from now.

This kind of exercise doesn’t predict the future. But it prepares you for it. It broadens the lens from short-term risk management to long-term worldbuilding.

⸻

Reflection

Max McKeown once wrote that “the work of strategy is shaping the future.”

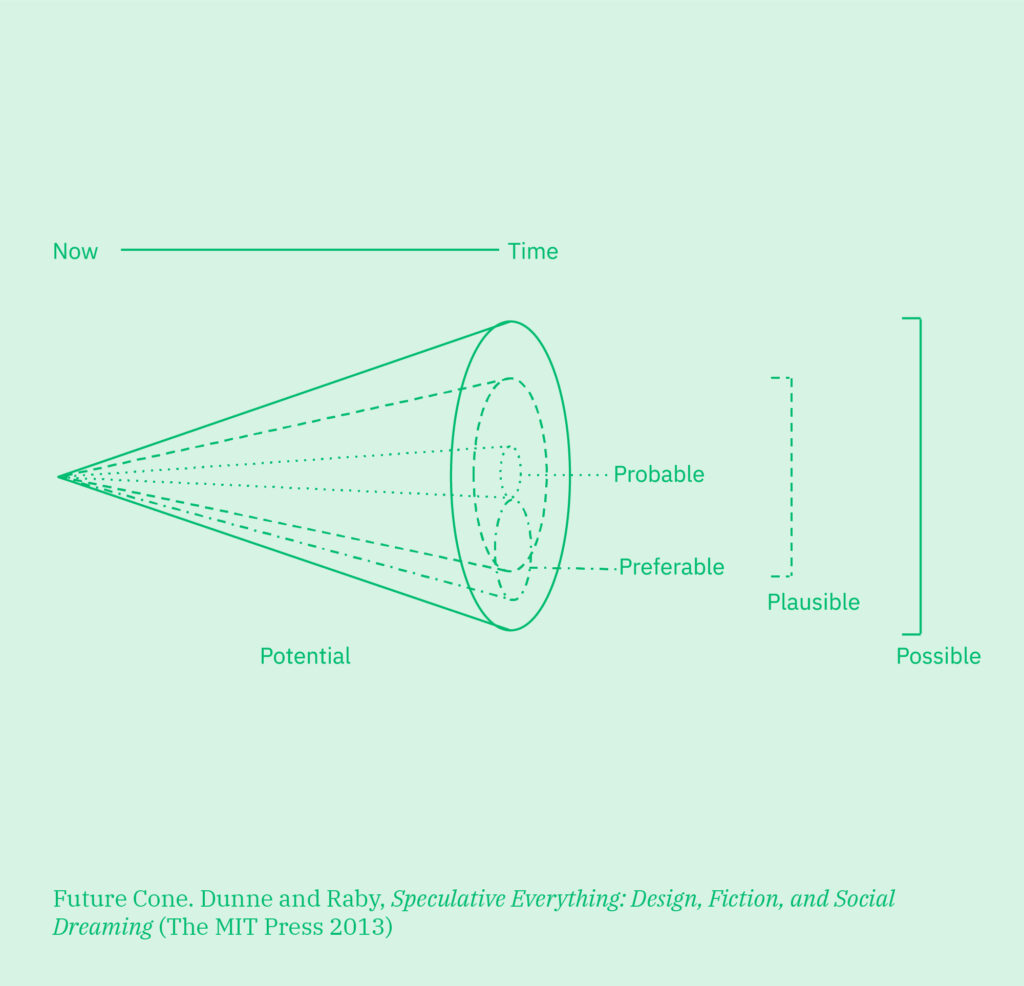

But too often, strategy gets reduced to chasing short-term gains. That path leads us to what futures scholars call the probable future or the one we get if we simply extend today’s trends forward.

What we need instead is more courage to articulate and pursue the preferable future or the one we actually want to live in. Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, in their work on Speculative Design, describe this as deliberately imagining alternatives that stretch beyond the probable.

When organizations limit “the future” to a three-to-five-year horizon, they constrain themselves to the probable. They optimize for survival in the present instead of shaping a different tomorrow.

Yes, we need three-year strategies. But we also need 20-year visions. Without the latter, the former risks becoming incremental steps toward a future no one truly wants.

⸻

An Invitation

How much is your organization really thinking about the future you want, versus reacting to the present you’re stuck in?

Are you staring at the rocks in the path, or are you lifting your gaze toward where you want to ride?

Maybe it’s time to balance short-term strategies with long-term speculation. To invest not just in adopting tools like AI, but in imagining the futures those tools might bring about.

Because whether we like it or not, every choice we make—every technology we adopt, every policy we set, every system we design—is shaping the world our children and grandchildren will inherit.

The question is: are we doing that shaping intentionally, or by accident?

Perhaps the next time we sit in a room talking about “the future,” we should pause and ask: “When we say future, what do we really mean?”

And maybe, just maybe, we should extend our gaze a little further out.